I must confess–I find it amusing when people talk about “the” design process as if there were one final absolute ultimate standardized process that always guarantees success. Hmmm! Even I’m not sure what that really is! In my mind there exist multiple flavors of a general “ problem identification/solution creation ” process or methodology, with different steps depending upon the company, industry, and individual characteristics of the designer, as well as personal range of experiences, and evolution of preferred methods.

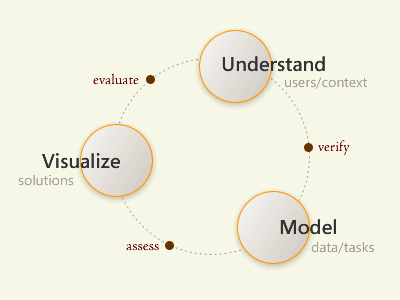

Fundamentally a design process features cyclical iterations. Not just iterations for the sake of iterating, but towards resolution, winnowing down multiple possible options (hypotheses) to get to the optimal/sufficient/viable solution for a given problem. It’s also cyclical–there’s a 360 degree revolution from start to finish, then starting again with different problems and situations (that may have emerged while investigating the initial issues, for instance). Or you may have to hop back up or jump ahead to other steps per emerging information or changing circumstances. It’s this fluidity and dynamism that I realize confounds non-designers (i.e., engineers and product managers). It’s not a recipe, nor a formula.

Also there’s something else that is difficult to pin down and quantify but must be accounted somehow: that serendipitous spark of brilliant creative insight, often expressed in terms of aesthetics but also it could be clever mechanics or nifty usability or a compelling story of use. To outsiders this must all seem quite confusing, chaotic, or even a bit mystical. Yet there is actually a general overarching pattern and structure, moving from problem to solution.

Here’s my take on the major phases of my particular flavor of “the design process”:

Understanding: a phase for becoming deeply informed about the users, market, industry, domain, competitors, as well as learning stakeholder concerns, issues, values, goals, etc. and ramping up on existing products if available. This will help identify the core problems and shape the personas, scenarios, and overall problem scoping. This is paramount. If you’re not solving the appropriate problems, then the entire design effort is in jeopardy. What is meant by “appropriate”? Depends upon the user, context, goal, task, etc. :-)

** Verify your personas and scenarios with real users and other stakeholders to ensure accuracy. (like the old adage, “trust but verify”)

Modeling: a phase for articulating the pieces that help in later design work, mapping out the objects and data/tasks/flows in the product or system, modeling the main workflows and tasks, and laying out the overall architecture of content and functionality.

These result in analytical artifacts, mostly diagrams for starting critical conversations and getting initial consensus and understanding/agreement from major stakeholders about the skeletal frameworks for the product (especially true for digital designs, web apps, software, services). Architectures are key here too: screen architecture, content structure, etc.

** Assess your models with Product Managers and Engineering leads for completeness of capturing and representing all the relevant tasks and objects and functions, etc.

Visualizing: a phase for actually designing possible solutions, with hand sketches, wireframes, mock-ups and prototypes all done as needed to help identify which options work best for your particular situation.

** Evaluate the visualizations (of whatever fidelity level) with your users via usability tests to catch usability problems, missed features, etc.

Hopefully issues of flow and architecture have been resolved by this stage, but more likely they will be often revisited as greater fidelity of the solutions emerge, especially at the prototype level. There needs to be a general understanding that phases can and often will need to be revisited but this should not be considered “failure” or “wasting time”. It’s all part of the practice of designing!

However, excessive re-addressing of design solutions should be avoided with the help of early upfront activities and artifacts like personas, scenarios, flows, and other items which help identify major requirements and so forth.

And as for that spark of creativity…personally I believe that true designers are always sketching and thinking and writing, jotting down options and alternatives, even when a phase isn’t “done” yet. Or if you’re leaping ahead downstream, that’s OK too. Naturally thoughts and images come to mind, just jot them down. Try things out. Sketching is a great way of probing and reflecting upon issues, just visually. It’s a way of freeing up your mind and getting ideas out there. A lot of it is just statistical: it often takes tons of ideas to get to that good one. So keep generating even while researching and meeting with stakeholders and drafting models/architectures. Developing this habit early increases the creativity potential (as well as open whiteboard brainstorming sessions with stakeholders), so I think it should be folded into “the process” from the beginning and doesn’t become a mad rush at the end to conjure up “the solution”.

So in the end, for me a well-thought out and compelling design solution results from informed understanding + personal ingenuity/creativity + collaborative inputs + technical viability + commercial value.

(I will most likely re-visit this equation, many times! :-)